Right then.

Not volunteering more than she had to

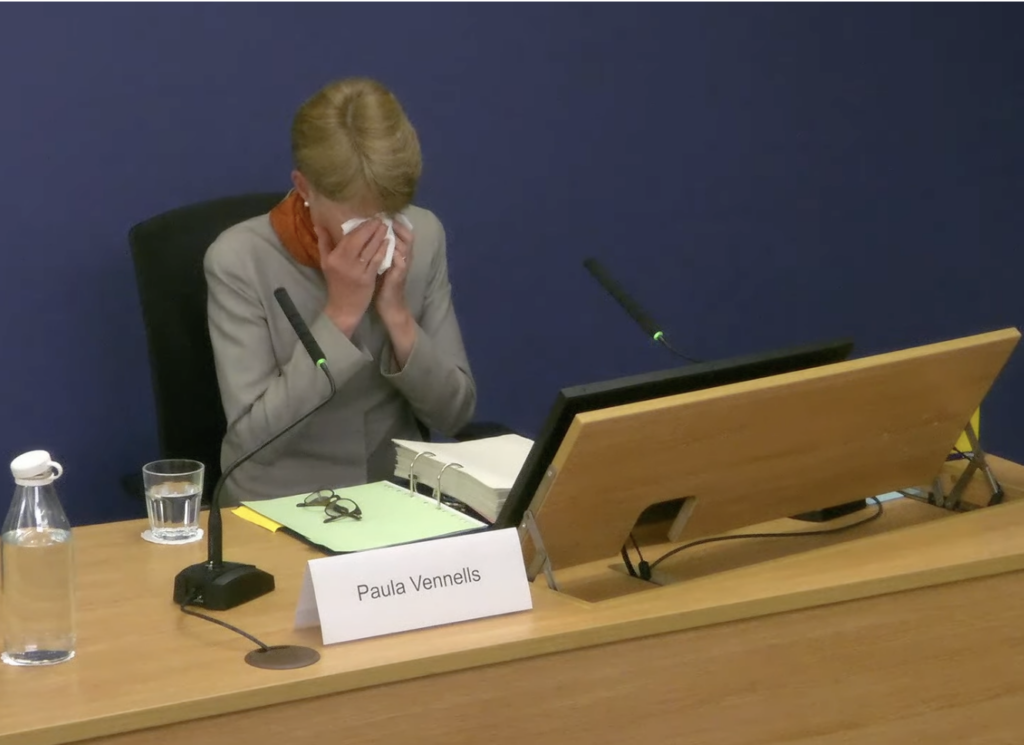

The fact that despite protesting several times she approached the inquiry with “integrity” in a spirit of wanting to tell the “complete truth” Paula Vennells appeared to be attempting a sleight of hand from the off.

Jason Beer KC (who asked questions on behalf of the Inquiry) reminded Vennells that in August 2023 the Inquiry wrote to her telling her that in her witness statement they would like her to: “reflect on your time at the Post Office and set out whether there was anything you would have handled differently”.

Beer took Vennells to paragraph 1801 of her witness statement, which states: “With the benefit of hindsight, there are many things I and the Post Office should have done differently. I am now reflecting with care on these matters and I will expand upon them and answer them as fully as possible when I give my evidence to the Inquiry.”

Beer was curious. “given you provided a 775-page witness statement that took seven months to write, could you not have reflected on what you could and should have done fully and differently within the witness statement?”

“Yes, I could have put more into it”, replied Vennells with a jolly, co-operative tone (which soon evaporated), “and I’m sorry if that wasn’t helpful. I read sooo many documents and worked a long time to try to prepare this.”

“Were you adopting a ‘wait and see’ approach? See what comes out in evidence? See what I’ve got to admit and then I’ll admit that.”

“No not at all Mr Beer”, replied Vennells, suddenly icy, “that’s not the way I work.”

“So…” returned Beer “why didn’t you assist us, by setting out in this document what your reflections were?”

“It was simply a matter of time”, replied Vennells.

Vennells offered to submit a written document of reflections to the Inquiry. Beer did not take her up on it.

Moya Greene 💔 Paula Vennells

Paula Vennells’ boss whilst she was Post Office MD was Moya Greene, the Royal Mail Group CEO. After the Post Office separated from Royal Mail in 2012, Vennells was made Post Office CEO. The two women maintained a cordial professional relationship for many years. That all changed this January during a text exchange.

Greene had flown back into the UK and obviously seen the parliamentary hoo-ha caused by the sacking of the Post Office Chairman Henry Staunton. On 16 January this year Nick Read, the current Post Office CEO, gave evidence to the Business Select Committee.

This is the full dramatic exchange of texts:

MG: Paula, am just back in the U.K. What I have learned from Inquiry/Parliamentary committee questions is very damaging. Nick was a poor witness. Chairman gone. He will be next. When it was clear the system was at fault, the PO should have raised a red flag, stopped all proceedings, given people back their money and then tried to compensate them for the ruin this caused in their lives. M

PV: Yes I agree. This has/is taking too long Moya. The toll on everyone affected is dreadful. I hope you had a good break and are well. BW Paula

MG: I don’t know what to say. I think you knew. m

PV: No Moya, that isn’t the case.

MG: I want to believe you. l asked you twice. I suggested you get an indépendant review reporting to you. I was afraid you were being lied to. You said system had already been reviewed multiple times. How could you not have known?

PV: Moya, the mechanism for getting to the bottom of this is the Inquiry. I’ve made it my priority to support it fully.

MG: The Post Office did not… they dragged their heels, they did not deliver docs, they did not compensate people. Paula… you appealed the Judge’s decision! I am sorry… I can’t now support you I have supported you to my detrment. I can’t support you now after what I have learned. M

Putting aside Greene’s curious teenage break-up vibe (and her possible motivations for initiating contact), Jason Beer wanted to know a little more about the central accusations. Firstly, what did Vennells know?

“Was that an accusation that you knew about bugs, errors and defects in Horizon?” pondered Beer.

“No”, replied Vennells, “She was trying to square her memory with what she was hearing. Yeah.”

“What did you think you were denying?” asked Beer.

“I think Moya was possibly suggesting there that there was some conspiracy… and as I said I didn’t believe that was the case. She may have been saying… I was going to say about a cover-up, but that’s the same thing.”

Beer drew her attention to Greene’s other, crucial, question – how could you not have known?

“You don’t answer that question do you?” he said.

Vennells agreed she didn’t answer that question but said it was more because she was concerned about exchanging texts in the middle of the Inquiry.

So, Beer, asked, what was the answer to that question? Vennells replied:

“It’s question I have asked myself as well. I have learned some things that I didn’t know as a result of the Inquiry and I imagine we will go into some of the detail of that. I wish I had known.”

“How come you didn’t?” Beer interjected.

Vennells started blethering about the Common Issues judgment and Horizon Issues judgment in Bates v Post Office, both of which landed after Vennells left the Post Office.

Beer had to stop her again. “But why didn’t you? That’s what I’m asking. Not whether you wish you had known. It’s why didn’t you?”

Vennells tried tacking towards management information… Fujitsu… people not sharing what they knew about Horizon’s integrity and some guff about corporate memory before Jason Beer gave up:

“Cutting through this”, he said, “this [text] exchange reveals that even the Chief Executive of the Royal Mail Group, who supported you over all those years, doesn’t believe you, does she?”

Vennells said Beer should ask her. Which he or a colleague almost certainly will when Moya Greene gives evidence on 19 July.

Trying to get the dirt on Martin Griffiths

Martin Griffiths was a Subpostmaster who sadly killed himself after being hounded out of his livelihood by the Post Office.

When news of Mr Griffiths’ death came through in October 2013, Vennells offered her condolences. In an email to her senior leadership team (including her head of security, John Scott), she said the Post Office should contact the family and “look after them as much as we can and as they will allow”.

Then she set a hare running: “I know (sadly from experience in business and personally) that there is rarely a simple explanation for such deaths; even though it is often easier for those so closely affected to look for one.”

Then, the kicker: “To help me brief this properly to the Board, can you let me know what background we have on Martin and how/why this might have happened. I had heard but have yet to see a formal report, that there were previous mental health issues and potential family issues.”

Oh. Ow.

Today Beer wondered if Vennells was asking her team “to look into Mr Griffths’ records to look for information or evidence that he took his life because of mental health issues, or family issues?”

Vennells took a moment to respond. She replied: “Mr Bates had said the Post Office was to blame, and I did know from previous examples and other information that…” there was a long pause… then, suddenly: “it doesn’t matter. I simply should not have said it. I should not have used those words.”

Some might have let the matter drop there. Not Jason Beer. And that is why he is lead counsel to the Inquiry.

Beer wanted to know who told Ms Vennells about Mr Griffiths’ alleged mental health issues?

“I believed I’d also seen something in an email somewhere, but I don’t recall.” replied Vennells.

“Was it rumour?”

“No I don’t believe so”, replied Vennells.

“Can you help us any more?” pressed Beer.

Vennells couldn’t, but did tell the Inquiry: “’Rumour’ would be a very inappropriate word”.

Could this have just been a terrible, single misjudgment made in the midst of some confusion?

No. The next day, Vennells was at it again. Emailing her senior leadership team, Vennells writes:

“I possibly heard (but may be confusing with a previous case) that Martin had had some mental health issues?”

Oh, Paula.

“How do you ‘possibly‘ hear something?” asked Beer.

“I’m simply stating an uncertainty”, ventured Vennells.

“Why are you saying this at all, if you might be confusing Mr Griffiths’ case with another case?”

“I was trying to make sure that there wasn’t confusion” replied Vennells.

“You were trying to get on the front foot here, weren’t you?” asked Beer.

“No, Mr Beer, that was not the case.”

“You were tasking the team with finding out information to counter any narrative that the Post Office was to blame, weren’t you?”

Vennells denied it and said she was just after “the wider picture”.

You decide.

Angela van den Bogerd is a Wingnut

For most of the 2010s, Angela van den Bogerd was the Post Office’s main woman dealing with Subpostmaster complaints and problems. At a recent talk in Walton-on-Thames, Ian Henderson (from Second Sight) described Bogerd as bright, able, hard-working and “completely brainwashed”. That is, unable to see the Post Office could be at fault for anything.

Today we found out that Bogerd was so completely insane, even the Post Office could not trust her.

A Subpostmaster called Heydi O’Brien had a Post Office in Griffithstown, South Wales. She had been a Post Office trainer for eight years and loved it so much she bought her own branch.

In 2014, Ms O’Brien and her daughter began experiencing balancing problems, which had clearly escalated. Ms O’Brien already had some contact with van den Bogerd, but wrote to Vennells out of “sheer frustration and desperation”. The rest of O’Brien’s email (which was not shown at the hearing) details the difficulties she has been experiencing.

Vennells gave oversight of the problem (and Angela van den Bogerd’s investigation) to her ops director Kevin Gilliland. Vennells told Gilliland: “I want to be really sure – not just on the individual case raised but as much on the issues Heydi identifies in the whole process around this.”

Vennells goes on: “Just watch that Angela doesn’t jump to any defence, or even worse assume she knows the answer (she did say to me the woman’s daughter had caused the problem). If we have been negligent in following through, we should think about how to manage it.”

Jason Beer wanted to know why Mr Gilliland was on notice to make sure that van den Bogerd didn’t “jump to any defence”.

Vennells gave a circumlocutory explanation which involved paying tribute to AvdB’s lengthy service, her “very deep understanding” and the fact she’d “come across most things”. Vennells acknowledged there was “a danger and a risk” that “people” could become “too close to something”, and might get drawn into “pattern of complacency” and “don’t necessarily see things afresh.”

Was it just AvdB’s length of service, Beer wondered, or was she “by default” a “Horizon defender”?

Vennells wondered aloud if AvdB had been “particularly defensive on something”, and noted AvdB had already started blaming Ms O’Brien’s daughter on what might be “assumptions”.

In short, AvdB could not be trusted to do a neutral evaluation. And Vennells knew it. And yet…

The remote access debacle

The final ninety minutes of Vennells’ evidence concerned her knowledge of remote access to the Horizon system and her email to her colleagues in the days before the Business Select Committee hearing on 3 Feb 2015 . Vennells was extremely cagey throughout this discussion, seemingly triangulating her answers against what she could say today, what she said on the record in the past and the actual truth.

Her famous message (first revealed at the High Court on 21 November 2018) of 30 Jan 2015, came under the Inquiry microscope. In the email Vennells addresses remote access to the Horizon system, and asks some senior people in her team:

“What is the true answer? I hope it is that we know this is not possible and that we are able to explain why that is. I need to say ‘no it is not possible’ and that we’re sure of this because of xxx and that we know this because we’ve had the system assured.”

Beer wanted to understand why Vennells had told her staff about the answer she wanted. In something which appears to have come straight from the Sir Humphrey playbook (and don’t forget her boss Alice Perkins was a former senior civil servant), Vennells replied:

“I can remember Alice Perkins saying to me at some stage, ‘Paula, if you want to get the truth and a really clear answer from somebody, you should tell them what it is you want to say very clearly and then ask for the information that backs that up’. That was why I phrased this that way.”

Beer was agog. “That’s an odd way of going about things, isn’t it? I want to know the answer to the question. Here’s the answer to the question. Tell me I’m wrong.”

There was laughter in the room as everyone contemplated Perkins’ and Vennells’ logic. Rather than distance herself from a ploy to get the answer you wanted rather than the truth, Vennells doubled down:

“This was a very genuine attempt to be able to reassure the Select Committee”, she told Beer. “I believed this was absolutely the case. I had an obligation going before the Select Committee to be able to share the information that I knew and to be able to answer their questions correctly and this is what I was trying to ask for from the team. I was not in any way – forgive me if you’re suggesting this – trying to tell them what the answer should be.”

Beer began to have fun. “I thought you said that’s what Ms Perkins said you should do.”

Vennells floundered: “Yes, but it was not done because I necessarily knew this was the answer. This was a…”

Beer interjected: “I thought you said a moment ago you believed it to be the answer.”

Vennells clung on. “I did believe it to be the answer and so I wanted to be able to say to the Select Committee in complete truth and sincerity that it was not possible to remotely access a branch account without the Subpostmasters knowing and I wanted to be able to explain why that was the case.”

Beer wondered if the more “honest and straightforward” thing to do would be to posit the question to her colleagues: What is the true answer? and stop there.

Vennells seemed to sense people were laughing at her. With strong head-girl-in-a-strop energy, she replied: “I’m very sorry, I am giving you completely the truthful answer on this. I remember why I phrased this this way. Not because I was trying to tell people what the answer was at all, but because I was trying to get them to phrase something in a way that said, from my understanding, this is what it should be.”

I am always inclined to try to be charitable to Vennells, but she was actually a lot worse than I thought possible. Like the organisation she ran, she seems to exist in parallel to actual reality. Delusional bubbles are fine for most of us, but they can cause problems when you have real power over real peoples’ lives. Either that or she was just lying.

Finally, if you want to watch Vennells tie herself in knots trying to deal with the best-timed single word question of the day, watch the last five minutes of today’s hearing. The Inquiry chair Sir Wyn Williams picks up on the briefing Vennells was given on remote access before the Select Committee hearing. It is devastating.

If you’d like to read all the live tweets and see the documents I’m referring to in the above blog post, click here.

If you want to read more about Vennells’ stewardship of the Post Office throughout the scandal, here’s a (hopefully) useful primer.

The journalism on this blog is crowdfunded. If you would like to join the “secret email” newsletter, please consider making a one-off donation. The money is used to keep the contents of this website free. You will receive irregular, but informative email updates about the Post Office Horizon IT scandal.

Leave a Reply