Damning evidence about the culture within the Post Office at the very highest level was brought to light during the course of Angela van den Bogerd’s second and likely final day of evidence at the Post Office Horizon IT inquiry today.

You can read my live-tweets and see the screenshots of documents posted up during the hearing here. For a summary of the lowlights, read on.

“Take a step back from the answer of an automaton”

Van den Bogerd started her career behind the counter of a Crown Office branch in 1985 just after leaving school. She rose to Director of Partnerships, before leaving in 2020. In all that time, she says, the most she contributed to the widest miscarriage of justice in UK legal history was by missing a few things in documents.

She is exactly the sort of person the Post Office likes. Long-serving, loyal, sharp and biddable. To get a measure of the sort of organisation she is part of, we were taken, at the beginning of the day, to the Post Office’s hounding of Martin Griffiths, a Postmaster driven to suicide.

Griffiths and his parents had poured tens of thousands of pounds into the Horizon-generated accounting holes in Griffiths’ branch in Hope Farm Road, near Ellesmere Port in Cheshire. At his lowest, Martin was attacked by armed robbers. The Post Office blamed him for that, too, initially demanding he give them the £38,000 that was stolen, later reduced to £7,600.

In a letter to the Post Office on 17 July 2013, Martin wrote:

“Over the last 15 months alone, February 2012 – May 2013, more than £39,000 is deemed to be my shortfall, an average of £600 per week. This surely cannot be correct, but the notifications from the Post Office state this is the case. The worry has affected [redacted] and plans for retirement have had to be postponed. I have not had a break in my business hours for more than four years, to keep a tight rein on the office. The financial strain on myself and my family is devastating and continues on a daily basis.”

Griffiths’ mother, who was in her eighties, also wrote to the Post Office around the same time, telling them:

“My son has been under severe pressure and I have personally had to take on more work in the retail side of the business, including providing financial support for the shortages. The so-called shortages over many, many months have been repaid mainly by myself and husband. Although you can continue to say there is no fault in the Horizon computer system, we eagerly await the results of the ongoing investigation being undertaken by Second Sight regarding software errors. Your letter of 3 July, stating termination of Martin’s contract, I feel is very harsh. Kevin Bridger [another Post Office employee] has compounded the severe problems adding insult to injury (and I mean injury), by requesting a fine of £7,600 which represents 20% of the robbery with violence which occurred in May. It was due to the identification of the culprit by a member of staff, that the Police were able to make a quick arrest and subsequently the robber received an 8 year jail sentence.”

By this stage Griffiths was in touch with Alan Bates at the Justice For Subpostmasters Alliance. When, on 23 September 2013, Alan was informed that Martin had deliberately stepped in front of a bus and was in a coma, he emailed the Post Office, with the family’s permission. Copying in Paula Vennells and Angela van den Bogerd, Bates wrote:

“I am aware of Martin’s case, and I know he was terrified to raise his shortages with POL [the Post Office] because of just this type of thing happening to him, but POL got him in the end. Regardless of what may or may not have occurred with him, why did POL have to hound him to the point of trying to take his own life? Why?”

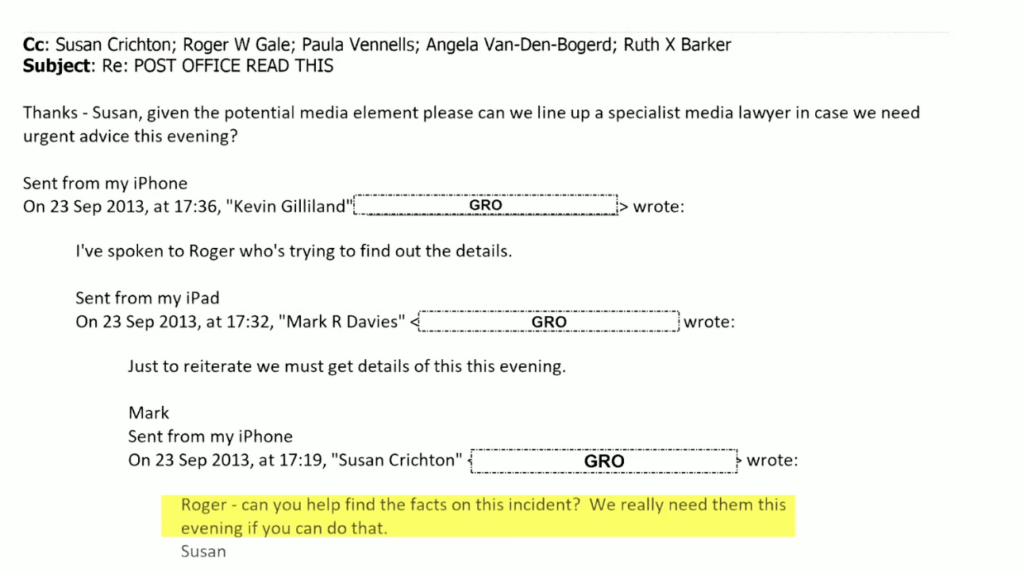

The Post Office’s reaction was telling. Any thought for the victim, his family, the community? This is the internal email chain which followed:

The top comment “given the potential media element please can we line up a specialist media lawyer in case we need urgent advice this evening?” came from Mark Davies, the Post Office’s then Director of Communications.

As Jason Beer KC, counsel to the Inquiry asked van den Bogerd:

“So the immediate reaction, you agree, is not – is Martin Griffiths alright? What about his health?… The immediate reaction was not – what can we do to help this man’s family?… What about his wife and his children, what about his elderly parents, what about his sister? Shall we get someone down to the hospital? No. The first things was – let’s get a media lawyer. Was that what it was like working for the Post Office at the time? It was all about brand reputation? About brand image?”

Van den Bogerd embarked on an explanation which involved conflicting reports about what happened. When pressed on the immediate reaction of her colleagues, she said: “I don’t think [PR messaging] was the first thought. It was definitely a consideration in everything that we did, around… you know, PR and the comms element.”

Beer asked why. Why was it important in this case? “A man has walked in front of a bus,” he said, “one of your Subpostmasters.” Van den Bogerd replied:

“In all my time with Post Office from very early on I was very conscious that PR was very important and everything had to be… it was a comms team… Mark was comms director at the time. And that’s what he said.”

After a year, Martin’s daughter, Lauren, wrote to the Post Office:

“I am emailing to let you know how disgusted we are with the treatment our family has received from the Post Office. As you are well aware it has now been almost a year since we lost our Dad. We hold the Post Office solely and wholly responsible for what happened to him. As I am sure you can imagine, our family has had an extremely tough year… I cannot comprehend how our family has not been supported or compensated this past year. I firmly believe that we would not have received this kind of treatment from any other large corporate organisation.”

The Post Office’s solution, approved by Angela van den Bogerd, was a £140,000 settlement offer to Martin Griffiths’ wife, Gina. To get it, she would have to drop any future claim against the Post Office, drop out of the Mediation Scheme and sign an NDA. The Post Office proposed sending the cash to her in instalments. Post Office lawyer Rodric Williams told Bogerd the Post Office asked for an NDA “as an incentive to Mrs Griffiths maintaining confidentiality. As drafted, if Mrs Griffiths were to breach confidentiality, we could stop any further payments but not recoup sums already paid.”

Beer paused his reading: “An incentive to maintain confidentiality. That was important for the Post Office, wasn’t it?”

Van den Bogerd said it was Rodric Williams who wrote the email.

Beer stopped her: “This is about a different issue. This about the Post Office staging payments to act as an ‘incentive’ to her – a sword of Damocles hanging over her. You don’t get any more money unless you keep quiet. That’s what this is, isn’t it?”

“That’s what Rodric is setting out.” Van den Bogerd agreed.

“Did you see anything unsavoury in using money in ensuring Mr Griffiths’ case was hushed up?” asked Beer.

“This was the first I heard of it from Rodric, and the fact that he said it was accepted, then I just allowed it to continue,” Van den Bogerd replied, confirming to the chair that she approved the way the offer was structured.

Beer wanted to know about the Post Office’s use of NDAs.

Van den Bogerd said: “Any settlement agreement the Post Office entered into was done with a Non-Disclosure Agreement”.

“Why?” asked Beer.

“Because that’s the way they operated, that was always…”

“But why?” cut in Beer. “Take a step back from the answer of an automaton. Why does the Post Office always insist on Non-Disclosure?”

“Because that’s how they tied up the agreement…”

“Yes but why?” pushed Beer.

“Well I just accepted that that was the standard approach with all settlement agreements and that was how they all operated and still do today I believe

“Does it like secrecy?” wondered Beer.

Van den Bogerd failed to give a coherent answer.

No evidence of theft

Tim Moloney KC devoted his allotted slot to questioning Van den Bogerd about her presentation of his client Jo Hamilton’s case to MPs on 18 June 2012. Among the MPs was James Arbuthnot, Jo’s MP. Bogerd agreed she had compiled the information about Jo’s case from looking at the prosecution files. She also agrees this is about the concerns MPs had about the integrity of Horizon and the idea people might have been wrongly convicted.

Bogerd had prepared a briefing pack containing a timeline of what happened at Jo’s branch in South Warnborough. Jo sat and listened alongside Moloney, as she does most days during the Inquiry. Moloney noted the audit and investigation part of the timeline, he listed the helpline calls, the agreements reached between the Post Office and the branch to settle outstanding discrepancies, then he notes the closing audit, the charge, the admission of false accounting and the eventual sentence.

“It was meant to be an open and transparent engagement with MPs, wasn’t it?” asked Moloney.

“Yes.” replied van den Bogerd.

Moloney pointed out that James Arbuthnot was concerned Jo Hamilton was not guilty. Bogerd agrees. Moloney took her to the front of the briefing pack where Alice Perkins, the new Chair of the Post Office says the purpose of the meeting is to give the MPs “all the information” they have available to address the MPs concerns.

Moloney then took van den Bogerd to a report written about Jo’s branch by an internal Post Office investigator called Graham Brander. The report noted several things. Firstly that overnight, between the auditor doing an initial check and a subsequent check the next day, a mysterious £61.77 added itself overnight to Jo’s £36,583.12 discrepancy. As the auditor could not explain this, it was just added onto the amount Jo owed.

Brander also wrote: “I was unable to find any evidence of theft, or that the cash figures had been deliberately inflated.”

Mrs Hamilton was charged with theft, a charge which was only dropped if she gave the Post Office £36k and made a statement which made clear she was not blaming Horizon for the discrepancies at her branch.

Moloney wanted to know why those details weren’t in her presentation to Arbuthnot. It led to this exchange.

“It was a snapshot of what had gone…. I don’t know exactly what I reviewed, but that information isn’t in what I presented.”

Moloney asked again why the “important… details” he listed did not appear in her summary. Bogerd began to squirm.

“The detail that you’ve just gone through was not the detail that… was made available to me, so I’ve taken what I understood to be the key points out of the information that was provided to be able to provide that synopsis of what had happened. I didn’t do an investigation at that point.”

“You didn’t need to do an investigation Mrs Van den Bogerd. The fact that there is no evidence of theft, says Mr Brander, and yet she was still charged with theft. Doesn’t that have to go into your summary so that this MP actually knows what went on with his constituent’s case.”

Bogerd changed her tune. “I don’t know if that was in the information that was made available to me at the time.”

Moloney cut in. “It was in the investigation report, Mrs van den Bogerd. You said you read that.”

Bogerd replied “I read whatever files we had that were available. I don’t know exactly what they were.”

And on it went. Bogerd was now not sure she read the full investigation files, some of the investigation report, or something completely different. Moloney wondered what documents she might have got her information from if it wasn’t the investigation report. Did she see it or not?

“I can’t remember exactly what I referred to,” she replied. “I just wanted to present the picture as I saw it from the information I had available.”

The Chair of the Inquiry, Sir Wyn Williams noted her summary just happened to support the Post Office’s perspective.

“That’s my recollection… I would have expected to have all the information provided to me at the time.” she volunteered, introducing a new mystery person who had come between her and the investigation files. “I don’t even remember who gave me the information.”

There are people like this in every organisation. They believe they are good people, and, outside of work, they often are, but they would quite happily exercise their corporate power to destroy an individual employee if a company executive demanded it, without it troubling their conscience one iota. And they are well rewarded.

“Did you get your bonus that year, Mrs van den Bogerd?”

At the end of the day, Sam Stein KC asked Mrs van den Bogerd about her treatment of Jennifer O’Dell, a woman who was repeatedly told by the Post Office helpline to pay for the discrepancy which appeared in her branch. It is worth reading Mrs O’Dell’s witness statement to the Inquiry to get a sniff of what she was put through. She has PTSD and night terrors.

By this stage Angela van den Bogerd had already agreed that the Post Office’s directions to its helpline operators was to tell people with discrepancies that in the first instance, Subpostmasters were told to make good discrepancies before any investigation as to how they might have occurred was initiated. Mrs O’Dell was repeatedly told to pay up. Angela van den Bogerd was in charge of the helpline. She oversaw a mass theft of Subpostmaster funds, based on an imbalance of power and blatant mis-stating of the terms of the Subpostmaster contract by helpline staff.

Stein told Bogerd O’Dell claimed that Bogerd was “bullying”, “intimidating” and that her home would be taken away if she didn’t make good the branch discrepancy. Bogerd was adamant this was not her.

Stein raised the issue of credibility, and the finding made by Mr (now Lord) Justice Fraser in the Common Issues judgment, thus: “Unless I state to the contrary, I would only accept the evidence of Mrs Van den Bogerd and Mr Beal [another Post Office employees] in controversial areas of fact in issue in this Common Issue trial if these are clearly and uncontrovertibly corroborated by contemporaneous documents.”

Mr Stein wondered if, when it came to clash of evidence, who should be believed. Van den Bogerd was again adamant that Mrs O’Dell was mistaken. Stein explored the Post Office’s response to the judge’s finding.

SS: What was said about you by Mr Justice Fraser was pretty serious, wasn’t it? Condemning you completely out of hand as being someone who simply he can’t trust. And he’s someone who has evaluated your evidence over quite some time in the witness box. It’s a pretty serious thing to hear about yourself, isn’t it?”

AB: Yes

SS: And the Post Office was obviously aware of what was being said about you? Yes?

AB: Yes.

SS: What did the Post Office do by way of an investigation into this? They must have looked into this. Did they?

AB: No.

SS: No? There was no discussion with you about – well hang on, that High Court judge said some pretty rum things about you, surely we should take this seriously. Nothing like that? Nothing ever done?

AB: No.

SS: No. I see. Alright. Did you get your bonus that year, in 2019, Mrs van den Bogerd?

AB: Yes.

SS: So despite a finding in the High Court – that basically you lied to the High Court – you got your bonus?

AB: Yes.

The sort of corporate culture which rewards people after they lied on the company’s behalf in the High Court tells you everything you need to know about that company and the individuals inside it. An organisation which actively supports employees who are evasive, withhold evidence and try to mislead a High Court judge is not that far from a criminal enterprise, which I guess is why it’s under criminal investigation by the Metropolitan Police. I don’t even think Angela van den Bogerd is a particularly special case.

Here’s a write up of part 1 of Angela van den Bogerd’s evidence.

I am currently touring Post Office Scandal – the Inside Story. Please do come and see us as we make our way around the country (all dates here).

The journalism on this blog is crowdfunded. If you would like to join the “secret email” newsletter, please consider making a one-off donation. The money is used to keep the contents of this website free. You will receive irregular, but informative email updates about the Post Office Horizon IT scandal.

Leave a Reply