The morning started on a light note. After Tim Parker had been sworn in, Jason Beer KC, who was asking questions on behalf of the Inquiry, took him to paragraph 268 of his 136 page witness statement.

Beer told the Inquiry that Parker had written about the Post Office appointing “a criminal with extensive experience to work alongside Brian Altman QC”. Beer wondered if perhaps the word “silk” was missing?

Parker agreed it was.

So, suggested Beer, “rather than the Post Office appointing a criminal, the Post Office would appoint a criminal silk?”

“Correct”, said Parker.

Glad that was tidied up.

Parker’s motivations for taking the job of Post Office chair were not properly explored. He told the inquiry he knew he was walking into a business “in deep crisis” and he showed some caution before agreeing to do so – requesting a good look at the Post Office’s figures. But Parker never took a salary (or, more accurately, he donated his salary to charity) which begs the question – why would a busy, important, incredibly rich man without a knighthood agree to take on this government-owned basket case for no money?

Parker’s due diligence only went so far. He had no idea his predecessor, Alice Perkins (and the business department and the Post Office board) thought Paula Vennells was a bit useless. In terms of his handover with Perkins, he told the Inquiry “I met Alice for lunch before I began.”

Parker has no recollection of any formal handover. Just a lunch.

Grooming the new chair

We were then taken to the briefing given to Parker on his arrival at the Post Office. It was drafted by Mark Davies, the Post Office’s director of communications. The initial draft of the document aimed to tell Parker that:

“thorough investigation has underlined that the [Horizon] system is efficient and robust.”

“We have also asked our external criminal lawyers to review all the cases involving prosecutions.”

“Throughout all this no evidence has emerged to support the very serious allegations being made”

“we only prosecute where there is clear evidence of wrongdoing… We do not prosecute people for making mistakes.”

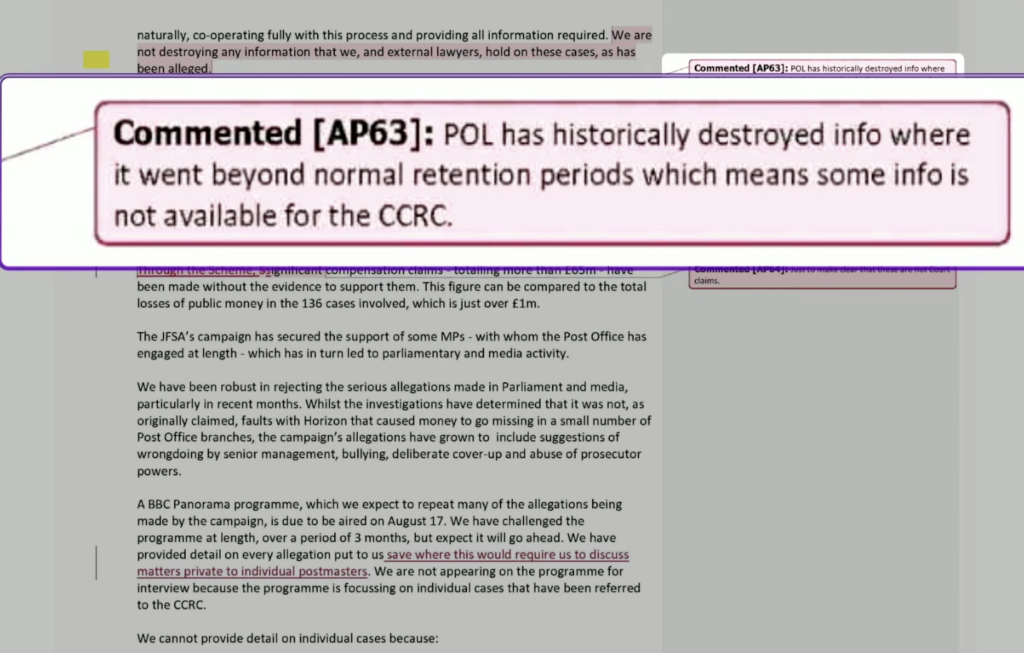

“Some… complainants have now asked the Criminal Cases Review Commission to examine their cases… we are co-operating fully with this process and providing all information.”

“No information at all has been destroyed, as has been alleged.”

All of the above statements are untrue:

- there had not been a thorough investigation of the Horizon system,

- the criminal lawyers had not reviewed all prosecutions,

- independent investigators Second Sight and Detica NetReveal and Deloitte had all found evidence supporting the serious allegations being made by the JFSA,

- the Post Office was not co-operating fully with the CCRC and had not provided all information (eg the Clarke Advice),

- information had been destroyed (a point we were told was picked up by Andy Parsons from WBD before the document went to Parker)

The briefing was eventually sent to Parker by his chief executive Paula Vennells, who claimed to be its author.

Tim Parker’s defence of his failings as Post Office Chair can be summarised this:

- it was a complex business with a lot going on. Potential miscarriages was only a part of what he had to deal with, and,

- had he known how many prosecutions and sackings there had been at the start, his response could have been different

- resolving the intractable issues raised by Subpostmasters could only be done in a court of law – Bates v Post Office was therefore a benevolent happenstance

- it was all Jane MacLeod’s fault

Quite Strong Language

Parker’s plans for helping Paula Vennells make the Post Office more commercially-minded were derailed by a letter he received from the Business Department shortly after he was appointed. Parker was told by Baroness Neville-Rolfe, the Post Office minister, that he needed to investigate the Horizon system and see whether or not there had been any miscarriages of justice. Neville-Rolfe told him:

“I am… requesting that, on assuming your role as Chair, you give this matter your earliest attention and, if you determine that any further action is necessary, will take steps to ensure that happens.”

Within a week of getting his feet under the desk, Parker appointed Jonathan Swift QC to write a report. You can read the Swift Review here. It’s not great, but it does suggest a lot of things at the Post Office have gone seriously wrong. Professor Richard Moorhead has written ten blog posts about its failings (start here). Parker, increasingly coming across as a semi-detached chair called the Swift Review “relatively reassuring”, telling the Inquiry: “it wasn’t a bad piece of work and it yielded some good recommendations”.

In his report Swift raises an essential point about the Post Office’s bait and switch prosecution tactic – going after Subpostmasters with unevidenced theft charges in order to secure a guilty plea of false accounting. As Swift has it, the Post Office “effectively bullied Subpostmasters into pleading guilty to offences by unjustifiably overloading the charge sheet”. Swift was unequivocal that this was “a stain on the character of the business.”

Beer said: “That’s quite strong language, isn’t it?”

“Quite strong, yeah”, replied Parker.

Secret Swift

Parker chose not to share the Swift Review with the Post Office board. He says this was because he was told not to by Jane MacLeod, the Post Office’s general counsel (the title given to a company’s top in-house lawyer). This apparently came down to Parker’s failure to understand privilege. Parker says he couldn’t do anything with the document because it was privileged.

Beer took him to this, noting “the report on its face is not marked as privileged is it??

“No, no”, said Parker.

“And the report does not say that it’s been provided for the purpose of… any ongoing litigation?”

“It doesn’t”, agreed Parker.

“It doesn’t say that it was provided for the purposes of obtaining legal advice, does it?” asked Beer.

“No”, said Parker, who (like most of us) had no idea what privilege is and the forms it can take.

It turns out Parker didn’t even give the Swift Review to Baroness Neville-Rolfe, his boss and the person who commissioned it. For this and his failure to give the report to the Post Office board, he was later censured by Sarah Munby, a senior official in the Business department. Parker said he was just following MacLeod’s legal advice.

When it came to the group litigation Parker also followed legal advice. He suggested that Bates v Post Office was not a failure, but somehow a natural consequence of the intractable problems the Post Office was faced with. Or as Parker said today: “it remains my view to today that once the litigation had started, and although I think we’ll see it wasn’t necessarily handled in the best and cooperative manner, the litigation… ultimately proved to be a comprehensive… settlement of a lot of very complex issues.”

Always the lawyers

Parker went on some after this, circling his point that essentially the courts were the best place to resolve the issues Alan Bates and the Justice for Subpostmasters Alliance had been raising. Beer waited until Parker had stopped speaking, then he asked: “Are you saying by that answer that it needed a group of brave and determined Subpostmasters to hold the Post Office to account by bringing in the Post Office before a court? And that the Post Office was incapable of doing it itself?”

It seems that was exactly what Parker was suggesting. He told Beer:

“with hindsight… the postmasters… Sir Alan Bates should never have been required to mount a group litigation order. I understand that… all I’m saying is that once it was in train, had it been managed a bit better, then a lot of complex issues might have been determined without the delay and without the cost. But a judge review of all these issues, I still think, one way or another, was the right way to get, you know, an outcome in the end, yes.”

Towards the end of the day, by Ed Henry KC asked whether he was being “fatalistic” about the scandal “and that more could have been done to strive to see the other side, and to strive for settlement without having to enter into the quagmire of litigation?”

Parker replied: “Yeah, I mean, there’s no satisfactory answer to this.”

Over the course of the day we were reminded that Tim Parker took on the job as Post Office chair by agreeing to give the company 1.5 days of his time a week. He then successfully managed to reduce that to 2 days a month. Just the man to run an organisation which he described in “deep crisis” at the time he joined, with “an awful lot going on… and an awful lot of stuff that needs addressing.” Challenged on this, Parker said:

“you asked the question… that somehow what happened here was the result of me not spending enough time at the Post Office, and I would certainly rebut that suggestion. I would say that I was a very active, energetic chair who took a lot of time and spent time with people to understand the business.”

The only way that logic could makes sense was if Parker’s reign was an unqualified success. As it was, he took the business from crisis into catastrophic failure, to the point that were it any ordinary organisation, it would be dissolved.

Parker’s shoulder-shrugging about the inevitability of litigation might have held more weight were it not for the fact that once the judge (Mr Justice Fraser) had begun to find in favour of the Subpostmasters, the Post Office threw the kitchen sink at trying to get him recused.

Parker says when Jane MacLeod suggested the Post Office attempt a recusal application, he was “a little bit uneasy… it’s big deal to get a judge to accept that they had made a judgment that was wrong on technical grounds”. Nonetheless, the Post Office went to the finest lawyers money could buy – Lords Grabiner and Neuberger.

According to Parker, Grabiner “said something along the lines that we had a duty almost to ask for the judge’s recusal….The way the advice was framed was that.. almost… the law required us, where we thought something had been incorrectly managed for whatever reason, we needed to act upon it.”

Grabiner’s claim that the Post Office had a “duty” to apply for recusal was described by Grabiner as nothing more than his personal emphasis, nothing to do with a legal duty. Beer asked Parker: “Can you recall whether you formed a view as in what sense you were under a duty to make the application?”

Parker replied: “I don’t want to make too much of this duty thing. I think we just got advice from two very, very senior lawyers and felt on balance that advice should be taken.”

Swift exit

The Swift report seems to have been strangled at birth by Jane MacLeod. She allegedly told Parker he could not release it to the Post Office board and then connived to ensure that the minister, Baroness Neville Rolfe, never got to see a copy. In fact – it was such a sensitive document it wasn’t initially digitised. According to Parker, under MacLeod’s instruction, the review was held in paper copy only by four people at the Post Office – MacLeod, Rodric Williams, Patrick Bourke and Mark Underwood.

Swift made eight recommendations including a proper review of the Horizon IT system. He also recommended every single Post Office prosecution should be investigated. Parker tasked MacLeod with implementing the Swift review. She, Williams and Bourke soon found an excuse to avoid doing so. When the Bates v Post Office litigation came around, Williams wrote of the need to create “a piece of advice that says TP [Tim Parker] should stop any further work”. Williams continued “I’m conscious that this feels somewhat unpleasant in that we are being asked to provide political cover for TP. However, putting aside the political background, shutting down TP’s review is, in my view, still the right thing to do.”

Patrick Bourke wrote: “the litigation makes the Review irrelevant since the issues to be considered will be put to a higher standard of testing in the Courts; to continue would be fruitless since we couldn’t use its output, senseless in terms of expenditure, and present unnecessary risk to the organisation’s legal position.”

Between them, they got their way. And what of Parker, the semi-absent, part-time chair?

“When you get to see these emails… which are what’s going on behind the scenes,” he said, “it kind of puts a different complexion on things”.

Jane MacLeod has refused to be questioned by the Inquiry.

The journalism on this blog is crowdfunded. If you would like to join the “secret email” newsletter, please consider making a one-off donation. The money is used to keep the contents of this website free. You will receive irregular, but informative email updates about the Post Office Horizon IT scandal.

Leave a Reply