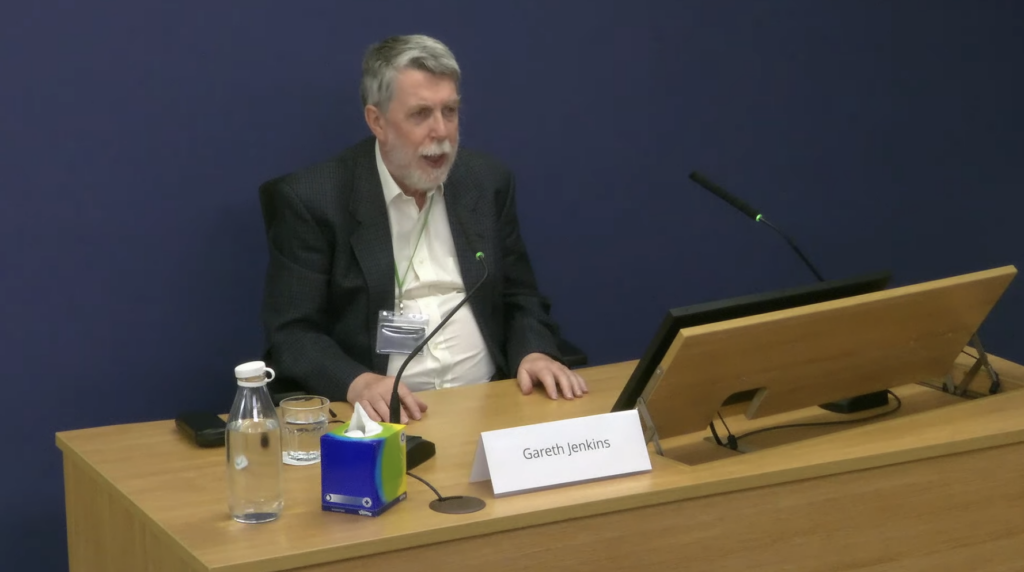

We know that Gareth Jenkins, Fujtisu’s “unreliable god” (in the words of Anthony de Garr Robinson) does not have a PhD – despite being erroneously described as Dr Jenkins in the first Clarke Advice and a number of Post Office documents. He does, however, have a maths degree from Cambridge. We found out today he was not and never has been a Chief Architect of Horizon, nor has he ever been Fujitsu’s Lead Engineer on Horizon. In terms of his career, Jenkins joined ICL (which later became part of Fujitsu) on graduating in 1973 and in the 1990s was recognised as a Distinguished Engineer, an honorific title bestowed on him by Fujitsu. Tuesday saw Distinguished Engineer Jenkins’ first of four days of evidence at the Post Office Horizon IT Inquiry, where he was questioned by the recently anointed Barrister of the Year, Jason Beer KC.

Beer asked him about his cv and wanted to know if Jenkins required any “further training or qualification or a particular professional experience that was required” before he could become a Distinguished Engineer? “Not as such, no”, replied Jenkins, who also seemed quite proud of having “resisted” any level of management responsibility throughout his career.

Jenkins vs Fraser

Gareth Jenkins was the first person since Lord Neuberger in 2019 to take direct issue with one of the judgments in Bates v Post Office. Neuberger didn’t like the Common Issues judgment. Jenkins didn’t like the Horizon Issues judgment. In his fourth witness statement Jenkins attempted to rebut the real and possible implied criticism made of him by Mr Justice Fraser. He prefaced this by saying “I have read the Horizon Issues Judgment of Mr Justice Fraser together with its Technical Appendix. I have reflected on the Judge’s findings and criticisms.”

Today he told Jason Beer “I skimmed through it at the time and I’ve looked at various sections of it, I don’t claim to have read it every word I’m afraid.”

This suggests Jenkins might not have written his witness statement, nor (like the Horizon Issues judgment) actually read it.

Beer asked him if he accepted Fraser’s conclusion that Legacy Horizon (the 1999 – 2010 version) was “not remotely robust”.

“I don’t accept that finding”, Jenkins replied.

“Do you accept that Horizon Online (the 2010 to 2017 version) was susceptible to accounting flaws?”

“There were some discrete bugs which caused problems to the accounts”, said Jenkins, “but they were all very well managed”. He felt Horizon Online did “a good job in terms of the accounting, particularly with the monitoring that was going on, in terms of being able to detect things when they had occurred.”

Beer wanted to know if Jenkins accepted that bugs, errors and defects caused discrepancies in Subpostmaster branch accounts. Jenkins replied: “They could cause discrepancies in branch accounts, but not at the sort of levels that are being talked about. In general, the systems, I believe, were operating as they should.”

“Robustly?” wondered Beer, possibly sarcastically.

“I think robust meant that there were mechanisms in place that would monitor what was going on, detect problems, and that they were then investigated and resolved correctly.”

“Horizon, both legacy and online, was working well in your view?” asked Beer.

“Most of the time”, replied Jenkins, adding “I’m not sure that I, even today, I understand what bugs actually did cause the problems that people have suffered from.”

It’s hard to know if this positioning by Jenkins is something he actually believes, or whether he has developed it as a defence strategy with his legal team to be deployed in a possible future criminal trial.

Someone’s lying

Jenkins claimed that Warwick Tatford, the Post Office barrister reviewing Jenkins’ witness statement during the prosecution of Seema Misra “wanted me to say that it looked as though Mrs Misra had stolen money rather than that it was incompetence.”

Beer wondered if Jenkins had seen Tatford’s evidence.

“I was actually here for that particular day”, sniggered Jenkins, perhaps pleased no one had recognised him.

Beer read out part of Tatford’s witness statement:

“I made it very clear to Mr Jenkins that he was under a duty to provide frank disclosure of Horizon problems to the defence expert in that case.”

“I have no recollection of such a discussion”, replied Jenkins.

“So his evidence here is in error, is it?” asked Beer.

“I can’t say categorically”, replied Jenkins. “That is not my understanding of what occurred at the time and I think I would have behaved differently if I had been briefed in the way that he suggests that he briefed me.”

Beer took him to Tatford’s oral evidence transcript, during which he explicitly stated he told Jenkins about his responsibility as an expert witness during the Misra trial, including the duty to “disclose anything that might undermine his position”.

Beer asked: “Did Mr Tatford make clear to you the duties that he spoke about?”

Jenkins replied: “I don’t believe he did.”

Far from being an unbiased, independent expert witness, Jenkins told Beer “I was an employee of Fujitsu and therefore was effectively part of the Post Office prosecution team.”

“Did you think you were part of the Post Office prosecution team?” replied a surprised Beer.

“Yeah, I think I probably did,” considered Jenkins “because that’s how the Post Office lawyers were treating me.”

The Whole Truth

Seema Misra’s trial took place in October 2010. Her defence team instructed an independent IT expert called Charles McLachlan. In his report, McLachlan sets out his qualifications and experience, the caveat that his report “shouldn’t be read as expressing any opinion on factual matters… or legal issues”. He also lists the documents he had been given, what he had been asked to do, and what he had not been asked to do. McLachlan also states his “overriding duty to the court”.

Jenkins, despite being the Post Office’s supposed independent expert, produced no such equivalent report, instead using a bog standard witness statement to comment on McLachlan’s findings.

Beer wanted to know why, at the very least, Jenkins made no mention in any of his witness statements in the Misra trial about any bugs, errors or defects within the Horizon system.

“I didn’t think I needed to do that”, Jenkins replied, “because all I thought I needed to worry about was in that particular branch at the time in question.”

“Did you consider reflecting in your witness statements or making qualifications in your witness statements to set out exactly what you had been asked to do and not asked to do and make clear that you had not been asked about other issues?” asked Beer.

“It didn’t occur to me I’m afraid.”

“Looking back now do you think that a reader of your witness statements could reasonably gain the view that you were setting out all that you knew about bugs errors and defects in Horizon?”

“I don’t think I was ever asked to consider bugs errors and defects, all I was asked to do was comment on the reports produced by Professor McLachlan.”

Beer pushed him on this.

JB: You would know that witnesses, when they come to give evidence, are asked to tell the truth and the whole truth.

GJ: Yes.

JB: Did you think you were only required to tell the truth in your witness statements?

GJ: I was, I was talking about those aspects that were related to the Horizon system and I believe I did tell the truth and the whole truth as far as the Horizon system was operating in the specific branches at the specific times that I looked at data.

JB: But you didn’t feel under any compunction to volunteer information about other faults or system defects about which you had not been asked?

GJ: I didn’t think that they were relevant in those particular cases.

JB: Just expand on that, you’re saying that you took a conscious decision not to mention them because of your own assessment of relevance?

GJ: Not a conscious decision, as far as I was concerned the system was behaving correctly in the branch at the time and I’d seen nothing to show that it wasn’t and therefore other issues that I may have been aware of were ones that had been that had gone on in the past or in the future and had been fixed and did not apply to the branch at the time that I was considering.

JB: Are you saying that in every case in which you provided a witness statement you had undertaken or caused to be undertaken a detailed examination of the data relating to that branch?

GJ: I’d undertaken an analysis of the data, not necessarily a completely thorough analysis of it, but I thought what I felt at the time it was sufficient to show that things were working okay at that time.

The Mask Slips

Jenkins’ attitude towards the Subpostmasters he was involved in prosecuting wasn’t that different to the people he was working with at the Post Office. During some early correspondence with the Post Office investigation team about Lee Castleton’s case, Jenkins tells Post Office investigator Brian Pinder he can’t comment on specifics without “a detailed analysis of everything that’s gone on in the branch.” Nonetheless, Jenkins confidently asserts, “the most likely explanation it’s a misoperation or fraud.”

“Why was it certainly the case that the most likely explanation was misoperation… or fraud?” asked Beer.

“I’m not sure why I would have said that at the time”, replied Jenkins. “Looking back now then I think that’s just one of many different options but I accept that those are the words I used at the time.”

“Why did you use them?” asked Beer.

“I don’t know”, Jenkins replied.

Pulling back the curtain

This Distinguished Engineer, this technical wizard, this “god” did not seem able to accept how badly he, Fujitsu and the Post Office had messed things up. And yet when Beer drilled down into how Jenkins reached his supremely confident views, the curtain was pulled back a little.

Firstly Beer established that Jenkins had no oversight of all the bugs in Horizon. No one at Fujitsu did. Jenkins was only aware of the few which were brought to his attention. Nonetheless, he told Beer:

“I was aware of was the fact that bugs that actually impacted the accounts were very rare. There was good monitoring in place to detect them and they got fixed shortly afterwards so in terms of what was actually there in the live system at any one time it was very rare for there to be bugs there that would cause problems and therefore I was confident in the way that the system was operating”

Beer asked him if this confidence was going to be expressed to a court “wouldn’t you want to know of the existence of each of the bugs and how they’ve been resolved and whether in fact there was any ongoing impact?”

“I didn’t realise at the time that I needed to do that, so at the time no”, replied Jenkins. “Obviously with hindsight I realised that maybe I should have been doing more research, but at the time I felt that that was sufficient.”

“And the ‘that‘ in that sentence meaning a general confidence in the system and the way that it operated?”

“Yes, and the processes that are in place to actually control things.”

“So general confidence in the system plus processes that you thought were working allowed you confidently to give a generalised view, is that right?”

“I think so, yes.”

Jenkins wore his superiority complex lightly. He remained fixed in his views that the Horizon system worked well enough to allow him to produce witness statements which were used in the prosecution of innocent people. Although he hasn’t been asked about it explicitly (yet), Jenkins’ conclusion that the Bates v Post Office Horizon Issues judgment was wrong implies he believes the people the Post Office successfully prosecuted were guilty, given it was the Horizon Issues judgment which allowed their cases to be referred to the Criminal Cases Review Commission.

Mr Jenkins’ evidence to the Inquiry will continue for the rest of this week.

The journalism on this blog is crowdfunded. If you would like to join the “secret email” newsletter, please consider making a one-off donation. The money is used to keep the contents of this website free. You will receive irregular, but informative email updates about the Post Office Horizon IT scandal.

Leave a Reply