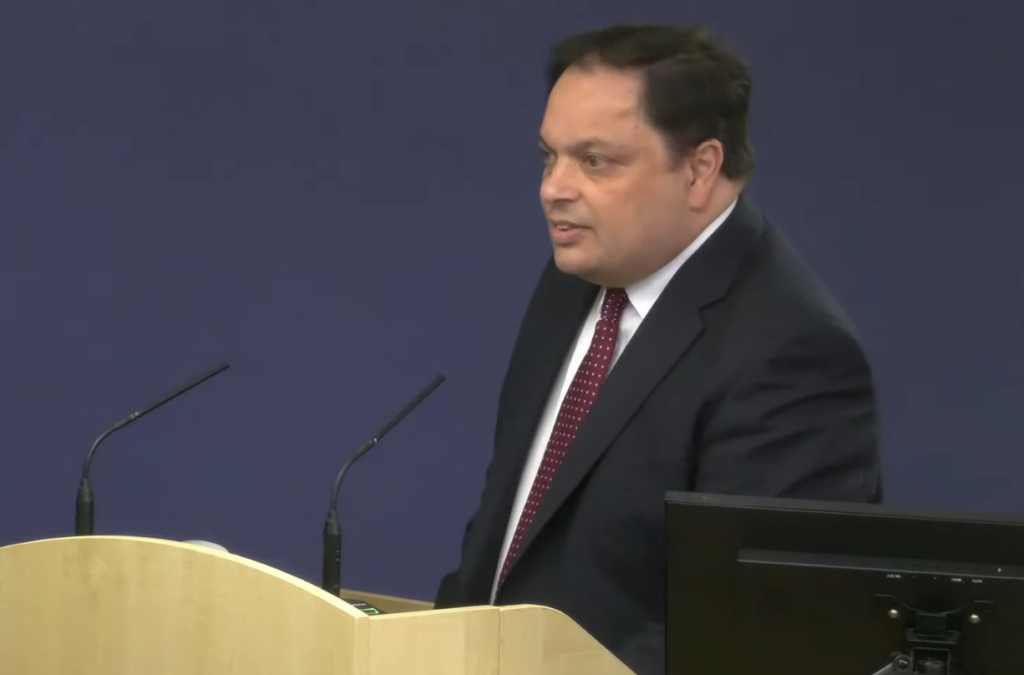

Fujitsu’s Andy Dunks has a problem. He signed dozens, possibly hundreds of witness statements attesting to the integrity of the Horizon IT system without, it seems, taking the relevant amount of care to see if the information he put in his witness statements was true.

These witness statements were used in the successful prosecutions of Subpostmasters. Today was about was probing to what extent Dunks knew (or should have known) the information he was presenting (or the way he was presenting it) was inadequate.

Unlike his previous appearance before the Inquiry, Dunks was given a reminder of his privilege against self-incrimination by the Inquiry chair, Sir Wyn Williams, at the beginning of the day. This suggests Dunks is now a person of interest to the ongoing Metropolitan Police investigation into this scandal.

Blurred Lines

Dunks’ job as part of the security team at Fujitsu was to turn round requests from the Post Office prosecution team. They would ask for data on the operation of the Horizon system and the logs of calls made to the Horizon helpline and they would dictate how much data was presented in Dunks’ witness statements.

Dunks was required to assert that the information he was providing was not only accurate but that it demonstrated the Horizon system was operating as it should.

Because Dunks admitted he had no expertise in the technical basis of the information he was being asked to supply to the Post Office, Dunks told the Inquiry he would discuss it with the experts at SSC – the Service Support Centre on the sixth floor of the Fujitsu HQ in Bracknell. This was where the third and fourth line support engineers were based, dealing with Horizon problems and fixing them.

Having discussed the call logs or ARQ (archive transaction and branch counter) data (mainly call logs in Dunks’ case) he would then write up his witness statement. Unfortunately, he claimed the knowledge and information he supplied to the courts in those witness statements as his own, rather than an understanding he had gained from speaking to colleagues.

Jason Beer KC, who asked Dunks questions on behalf of the Inquiry, wanted to know more.

“Did you realise when you were undertaking that task, going off to speak to, or speaking down the phone to people in the SSC, writing things in your witness statements that were based on what they were telling you, about which you had no clue yourself, that you were blurring lines?”

Dunks did not understand the question, so Beer tried again.

“When you were doing this, writing witness statements that were in part based on what other people had told you, the facts themselves, you yourself, could not speak to from your own personal knowledge. Did it occur to you that you were blurring lines?”

“No.” replied Dunks.

Peach and Chambers

We know that after SSC engineer Anne Chambers had given evidence in Lee Castleton’s case, the manager of the SSC, Mik Peach, refused to allow his staff to give witness statements, as Chambers had found the whole experience unpleasant.

Beer wondered if Dunks had ever considered the strange position he was in, providing sworn witness statements to the courts on the basis of second hand information provided by a team of people – the experts – who themselves were refusing to give evidence themselves.

“No I don’t, I didn’t see it like that, no,” he said.

“Did you think at all as to why the SSC didn’t want to go to court anymore?” probed Beer.

“I can’t remember my thought process, but I do remember that Mik Peach was quite protective of his team in all respects of doing things”, answered Dunks.

There is no evidence of Dunks having conversations with people in SSC. He said he wouldn’t call his colleagues – he would often go up to see them on the sixth floor. He didn’t take notes of the conversations or refer to them in his witness statements, but he was, of course, relying on them to inform the knowledge in his witness statements, which begged the obvious question from Beer:

“Would you agree, Mr Dunks, that you from your own perspective… you could not say that what you were being told [by your SSC colleagues] was right or wrong?”

Dunks agreed he had to “rely” on what SSC told him “because these are the people who dealt with these calls”.

“You yourself couldn’t know whether what they were telling you was right or wrong?” asked Beer.

“Yes, I suppose so yes”, agreed Dunks before applying some impressive mental gymnastics to tell Beer that because he had been told what was going on by SSC, that knowledge had become his. Or in his words: “once I’ve spoken to those people or asked questions about this, that and the other, I had that understanding. So it was within my… own knowledge.”

Flawless routine

What is extraordinary is that in his decade-long stretch of providing witness statements to the courts for the criminal prosecution of Subpostmasters, Andy Dunks did not once find a single call to the Horizon helpline that suggested IT error might be to blame for a branch discrepancy. Every single call was, according to his witness statement of “a routine nature”.

Beer explored Dunks’ methodology for doing this. A common assumption was that if the call from Fujitsu SSC was referred to the Post Office’s National Business Support Centre (NBSC) then it was not a technical fault, but a business issue or user error, especially if the call was not bounced back to Fujitsu from NBSC.

This noted Beer, involved two assumptions. That the diagnosis by SSC was correct, and that NBSC properly dealt with the call. Dunks agreed.

Beer then wanted to know about the boilerplate statement of truth which Dunks attached to every witness statement. He took it from a template which had lettered paragraphs. The paragraphs were apparently swapped in and out of each witness statement provided by witnesses at Fujitsu as required. In one version of the template statement, paragraph Q states:

“There’s no reason to believe that the information in this statement is inaccurate because of the improper use of the computer. To the best of my knowledge and belief at all material times the computer was operating properly, or if not, any respect in which it was not operating properly or was out of operation was not such as to affect the information held on it. I hold a responsible position in relation to the working of the computer.”

It does read like dreadful legalese because it is. Beer asked if Dunks was required to include this paragraph in his witness statements.

“I don’t know that the requirements were”, replied Dunks.

“Why did you include it?” asked Beer.

“Because it was in the witness statement template that we were told to use”, said Dunks.

“How did you know whether it was true or false?” asked Beer.

“Well, actually I don’t”, conceded Dunks, before realising what he was admitting to. He then suggested the paragraph was expressing his view that everything was “operating as it should and as it’s expected.”

Beer wanted to know what the “it” was in Dunks’ sentence.

“The counters and…”

“So stop there. You believe when you signed a witness statement that included that paragraph that it was testifying to your belief that the counters were working properly?”

Dunks agreed – he added that “it” also meant data integrity. Beer wanted to clarify.

“So this is providing a view, an opinion, an assessment on Horizon itself in your mind?”

“In respect of the branches and integrity of data, yes, in my opinion”, responded Dunks.

“I’ll ask again, how would you know whether that was true or false?” asked Beer.

“I would have made that my opinion based on the investigation that I carried out.”

“How could you tell, how could you say there was no reason to believe that the information is inaccurate because of improper use of the computer?”

Dunks did not know. He agreed it was an “assumption” based on his “opinion on an individual basis of every call that I looked at, and I was being asked for an opinion and that was my opinion.”

Beer reminded Dunks that in his witness statement he said that paragraph Q related only to: “confirming that I had not improperly used the audit extraction software to manipulate the data I was exhibiting and that as far as I was aware the software had run properly when extracting the data.”

In fact, Beer noted, Dunks went further in his witness statement to explicitly state: “I did not believe I was verifying that the system as a whole was operating properly at all times or that there could not have been any software errors that affected any of the information held within it.”

Dunks agreed that’s what he meant.

Beer took him to a review Dunks conducted of the data in the South Warnborough Subpostmaster Jo Hamilton’s case. The call logs and summaries of their content had been appended to Dunks witness statement.

Graham Ward, a Post Office investigator, emailed Dunks after reviewing an electronic copy of his witness statement.

Ward spotted a call made by Hamilton in 2004 to the Fujitsu helpline. It was recorded as a “critical NT error” by the helpdesk operator. Ward told Dunks that this entry in the helpdesk log “appears to suggest a fault.” He asked Dunks “Can you simplify what this means?”

Dunks agreed to do so, and there, it seemed, the paper trail ended. The witness statement was not updated. But Dunks insisted to Beer he would have carried out an investigation before deciding not to update his witness statement. Beer wasn’t sure about this. He took Dunks to the call log in question and noted that it referred to two entries in the Known Error Log, one of which suggested the error had multiple causes and multiple potential solutions. Beer asked Dunks:

“So reading the entry on the helpdesk and reading these two KELs which… you would have done, how were you able to say that what you read did not disclose anything other than the system operating properly?”

“I’d had discussions with someone within the SSC to explain what was going on. We’d looked at the call to see what the steps were, and I mean this is a known error log, so these errors have been seen before”, said Dunks, a little lamely.

“Is that a good thing?” asked Beer. “How were you able to say that this had no effect on the proper operation of Horizon?”

Dunks waffled. “It was still working as expected. There may have been a fault at the counter, but again, that’s within the boundaries and integrity of the Horizon system. I believe… in my opinion… at the time it was working as it should do and there wouldn’t have been any integrity issues with the data between the branch and the Horizon.”

“Did you look at the data to see whether there were any integrity issues?” asked Beer.

“At the data?” asked Dunks.

“Yeah.”

“No.” replied Dunks.

Page Cut

Dunks came completely unstuck when he was questioned by Flora Page, a barrister representing Seema Misra. Page took Dunks to a witness statement he submitted in the Misra case on 29 January 2010, in which he told the court “I can confirm that all the calls mentioned from West Byfleet Post Office to the Horizon System help desk are of a routine nature”.

The Witness Statement appeared to have been printed out alongside an email chain between Anne Chambers and Gareth Jenkins (two SSC engineers). In reviewing the West Byfleet branch date Chambers told Jenkins:

“There are several entries on the 1 Sysman 2 126023 tab which require some further investigation. I’ve added some highlighting.

“Counter 1 on 2/3 May 2006, and 4 Feb 2008. I don’t know whether the counter was replaced, or whether the messagestore was deleted and copied from another counter. The Powerhelp/TfS calls may illuminate this.

“I don’t know if the counter was used while these errors were occurring. It may have been. If they have any complaints specific to these times, perhaps they should be checked out???”

Page told Dunks that Chambers “makes it absolutely clear that the calls [to the helpline by Seema Misra] required some technical investigation and some cross-checking [of the ARQ data] to find out what lay behind them and whether they were indeed ‘routine.”

Dunks agreed that’s the intent behind Chambers’ email. Page then showed Dunks how the email chain reached him, via a message from his colleague in the Fujitsu security team, Penny Thomas. In her email Thomas told Dunks: “I requested the events to be checked to support your witness statement; I’ve had a chat with Gareth this morning and as no transaction data has been requested it is pointless going further with the exercise. However, you may like to check Anne’s comments against the calls in your witness statement.”

Page asked Dunks: “Would you accept that when you were sent this email chain, it put a burden on you to check your witness statements and make sure that what you’d said in them was correct and not misleading?”

Dunks agreed wholeheartedly, saying: “Well, that would have been my… process throughout.”

Page made sure: “So you say now, do you, that you did all the work that was set out in Ann Chambers’ witness email here?”

“I hope to think I did. I don’t remember what that involved and what I did specifically”, said Dunks.

Page pointed out his problem. “At this time there was no ARQ data. How would you have done it?”

“I had the data to carry out and to be able to make that statement. So I had the data.” countered Dunks.

“You had the call records. but you didn’t have the ARQ data, it hadn’t yet been produced.” said Page.

Dunks floundered. It was hard for him to suggest he’d done a proper (any?) investigation without the data he needed to do it. “I can’t remember what I would have done,” he tried, “but I would have done something.”

Page was having none of it: “Well, we do not see, do we, a further witness statement in which you qualify or say anything at all about the statement that we’ve just had a look at, in which you claim… all the calls were routine.”

“If the statement didn’t need updating, because that statement was in my opinion still true, there was no update needed”, replied Dunks, using the same tack he’d adopted before lunch with Jason Beer. But this time there was no escape.

“How could it still be true when those investigations had not been carried out and could not be carried out?” demanded Page.

“Well, I’m sorry,” said the skewered Dunks, “but I would have done checks.”

With his witness statements giving succour to the courts that there were no problems with the Horizon IT system, Andy Dunks condemned several dozen innocent Subpostmasters to lives of penury and anguish. There is not a shred of evidence to support his repeated claims of diligent investigation behind the statements he produced for the Post Office. I understand the well-tanned Mr Dunks is taking a holiday next month to experience the Olympics in Paris. He is still employed by Fujitsu.

The journalism on this blog is crowdfunded. If you would like to join the “secret email” newsletter, please consider making a one-off donation. The money is used to keep the contents of this website free. You will receive irregular, but informative email updates about the Post Office Horizon IT scandal.

Leave a Reply